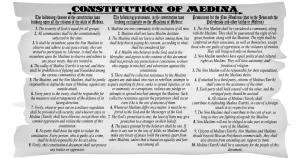

Law is a practical system of rules and remedies created to balance competing social interests, reflect shared moral expectations where possible, and provide authoritative procedures for resolving disputes.

Why a “workable” definition matters

Legal theory offers many abstract definitions: law as sovereign command, law as moral order, law as social facts, law as policy. Each is useful for certain arguments but none alone is sufficient for everyday legal reasoning or teaching. By “workable” we mean a definition that is short, actionable, and descriptive enough to guide scholarship, judicial reasoning, and public understanding. This article explains the nature and functions of law in accessible terms, contrasts key schools of thought, and offers a concise formulation that is practical for scholars, students, judges, and civic-minded readers.

The nature of law — layers, not a single essence

Law is best understood as a layered phenomenon. At one level it is text: statutes, codes, regulations, and contracts. At another level it is practice: enforcement, litigation, and adjudication. At yet another level it is normative expectation: social beliefs about right and wrong that influence legal content and compliance.

What Does Mean By Human Rights?

These layers interact. Text without enforcement is weak; enforcement without legitimate norms risks tyranny; norms without clear procedures produce unpredictability. Recognizing these layers allows a workable definition to accommodate both formal requirements (what courts must apply) and informal realities (how people actually behave).

Law as social engineering — the functional view

A highly practical way to understand law is to see it as an instrument of social engineering: a toolkit designed to shape behavior, allocate burdens and benefits, and prevent or resolve conflicts. From this perspective, lawmakers and judges are engineers who design rules and remedies to steer social outcomes toward stability, fairness, or efficiency, depending on the political and moral preferences in play.

Key consequences of this view:

- Law is purposive: rules exist for reasons (safety, commerce, justice).

- Law is responsive: good legal design adapts as social conditions and values change.

- Law is evaluative: success is measured by outcomes—compliance rates, fairness, social welfare—not merely textual fidelity.

This functional emphasis makes the concept applicable to regulatory policy, contract design, and constitutional reform alike.

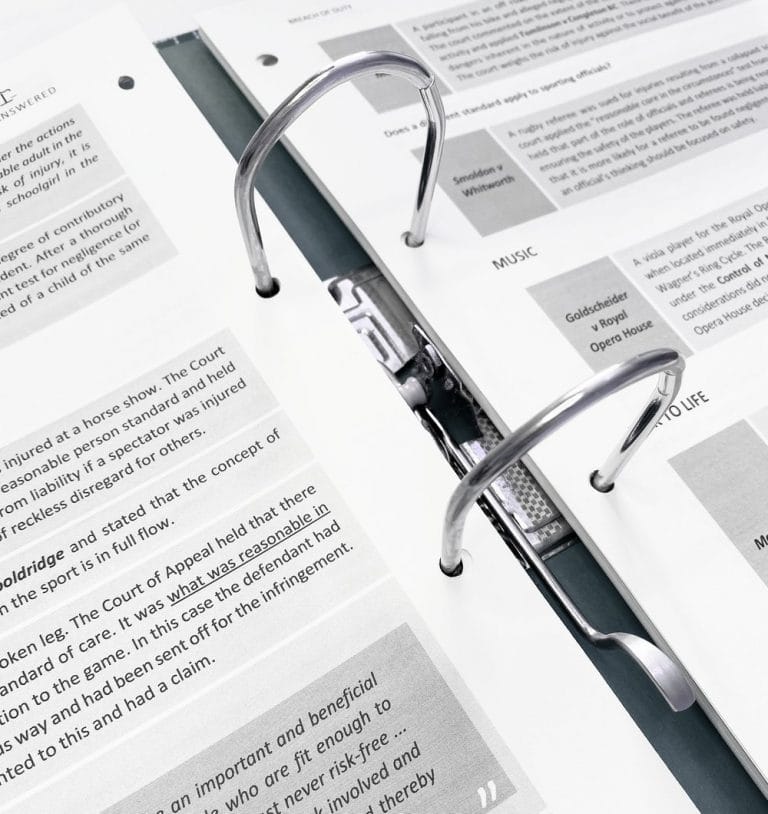

Legal realism — judges, interpretation, and the human factor

Legal realism highlights the decisive role of judges and administrators: law is not applied by machines but by people with discretion. Realists argue that outcomes depend heavily on how judges interpret texts, select facts, and weigh policy considerations. From a workable standpoint, this implies:

- Any practical definition must account for interpretive discretion. Rules are tools; judges decide which tool to use and how to calibrate it.

- Predictability requires not only good rules but also transparent interpretive methodologies and institutional incentives that constrain arbitrary discretion.

- Training, precedent, and procedural safeguards (appeals, reasoned opinions) are crucial components of the legal system’s effectiveness.

Thus, a workable definition should treat judicial practice as part of the law, not merely as an external application.

The ends of justice — purpose and limits

Law aims at multiple ends: order, liberty, equality, and the protection of legitimate expectations. These goals sometimes conflict. For instance, strict enforcement of contract terms may promote economic predictability but can produce harsh results in exceptional circumstances. A practical definition must therefore recognize trade-offs and the unavoidable presence of moral judgment in legal decision-making.

What Is the International Bill Of Rights?

Two pragmatic rules follow:

- Law should provide consistent baseline protections (due process, basic liberties) that cannot be lightly overridden.

- Law should allow context-sensitive remedies where strict application would defeat the ends justice seeks to achieve.

This balance is why legal systems include doctrines like equity, discretion, and proportionality.

A concise, workable formulation

Putting the above together yields a compact working definition:

Law is an organized system of written and unwritten rules, backed by recognized authority, designed to regulate conduct, resolve disputes, and distribute social entitlements and burdens—operationalized through institutions (legislatures, courts, regulators) that interpret, enforce, and adapt those rules to changing social needs.

This definition emphasizes system, authority, function, and institutional operation—elements that make the concept usable in both analysis and practice.

Common critiques and limitations

No single formulation can capture every jurisdictional nuance or theoretical dispute. Typical critiques include:

- Over-inclusiveness: Some argue this definition is too broad and risks collapsing law into general social norms.

- Moral indeterminacy: Critics from natural law insist that a workable definition that omits moral foundations is incomplete.

- Institutional variance: Different legal families (common law, civil law, religious law) operationalize rules differently; a single definition may understate these differences.

A workable approach accepts these critiques while remaining practically oriented: the definition is meant to facilitate legal education, policy design, and comparative analysis—not to resolve deep metaphysical debates about the nature of law.

What does the Rule of Law mean, and what are its fundamental principles?

Practical recommendations for scholars, students, and practitioners

- Use layered descriptions: When teaching or drafting, state textual rules, enforcement mechanisms, and prevailing social norms separately.

- Prioritize clarity: For public-facing definitions, favor short working sentences that explain purpose and mechanisms.

- Document interpretive choices: Judges and lawyers should explain how policy considerations influenced their readings—this improves predictability.

- Design for adaptability: Lawmakers should build review mechanisms (sunset clauses, impact assessments) into novel regulations.

- Cite cross-national practice: Comparative examples often illuminate how institutional differences shape legal outcomes.

A workable definition of law must be both descriptive and instrumental. It should map the rules people follow, the authorities that enforce them, the institutions that shape their meaning, and the social goals those rules seek to achieve.

By combining layer-based analysis, a functional view of law as social engineering, and attention to judicial practice, the concise formulation offered above becomes a practical tool for teaching, analysis, and reform.

FAQ on Workable Definition of Law

What is a workable definition of law?

A workable definition: an organized system of written and unwritten rules, backed by recognized authority, designed to regulate conduct, resolve disputes, and distribute social entitlements and burdens through institutions that interpret, enforce, and adapt rules.

How does legal realism affect the way we understand law?

Legal realism emphasizes judges’ interpretive role, arguing that outcomes depend on judicial discretion and practical reasoning. A workable definition includes judicial practice as part of the law.

Why is law described as social engineering?

Because law functions as a toolkit to design social outcomes—allocating rights, guiding behavior, and resolving conflicts—so lawmakers act as engineers shaping social policy through rules and remedies.

What are the limitations of a single definition of law?

A single definition may be overbroad, omit moral foundations, or understate institutional differences across legal systems; it serves best as a practical starting point rather than a final metaphysical claim.